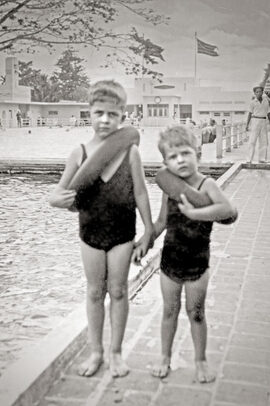

The author's father with older brother, Ed and the author

chapter 1

Medan

Haiku of contents

Birth, green jungle, storm.

Plantation life, animals,

Musinem, mommohs.

Extract

During that early period, I remember we had two dogs, dobermans named Tommy and Moppie – black, swift fires of anger, although in our presence, they were simply pussycats. The servants feared them despite the dogs sleeping in their quarters. One day, Tommy, who was a crazy fighter, engaged in a duel with a wild pig on the road in front of our house, a road which was no more than a clearing cut through the jungle some years previously and which saw only the occasional car and a few slow-moving grobaks scattering loose gravel. His guts hung half out of his body yet he tenaciously clung to the throat of the screaming pig until it died. Poor Tommy survived that fight. We had him stitched up by a dukun who swore all the time that no-one should have a dog which fought like a 'setan' (devil). The pig became dinner, thin slices of wild pig dried on the roof of the servants' quarters in preparation for dengeng, a delicacy which still makes my mouth water and is one of those yearnings which runs in the blood of the exile. Tommy's escape from an almost certain death on that occasion proved to be only a brief postponement.

One weekend, (it must have been a weekend because my father was home and away from the plantation), Tommy had gone missing early in the morning. My father and a small posse which included my older brother and me, went looking for him in the jungle, calling his name continuously. As we descended a slippery path into a kampong (village settlement), we heard barking, ferocious yet carrying within that ferocity, the hint of whining. We found Tommy, tied to a post, almost hidden amongst a cluster of small bamboo houses. There he was minus a leg, black tar smeared over where once a leg had been ( to stop the bleeding, no doubt). The Bataks were dog eaters - in Balige dog meat was sold openly in the markets – and poor Tommy was stolen and destined to be eaten, piece by piece. We hurriedly untied him and made our way through the jungle back to our house. Poor Tommy, however, weakened and perhaps infected by the amputation, did not survive the journey. I remember blood slowly trickling from his mouth, his eyes rolling backwards, his body convulsing – and then nothing, just total stillness. I had witnessed my first death, the departing of the soul. I burst into a torrent of tears, tears not of pity or love, but of pure and total rage, anger at the God who could allow this to happen, anger at us humans who claimed an intelligence superior to animal intelligence but yet nearly always betrayed ourselves.

Chapter 2

Malang

haiku of contents

Saidja and Rawi,

Chopin and a homecoming.

House and car, a bird.

Extract

This was the home in which my mother felt most at ease; where days would be spent organising her household and playing her beloved piano and where she could give her memories free reign and where she could re-establish herself. Prior to her marriage to my father (her second marriage) she had been a concert pianist, touring the European continent with her performances. She had been a pupil of Alfred Cortot, renowned French pianist whose special in- terests were the Romantic composers, in particular, Chopin and Schumann, with the consequence that these were my mother’s preferred composers as well. Her dream of re-establishing her professional musicianship was, to a degree, realised in Malang where she secured a weekly radio spot playing Chopin on the NIROM (Nederlandsch-Indische Radio Omroep Maatschappij), accom- panied by Dan Koletz and his orchestra. She continued playing and discussing Chopin’s life and music on her weekly spot right until the time of the Japanese occupation when the station was shut down. Her love of Chopin was passed on to me and he became my favourite as well. Often in my younger days, I would imagine playing his music, and he looking down, would smile at me.

Just recently, I happened to be in a bookshop and spotted a book about Cortot at whose house my mother lived when she was his student. For some reason, I had always imagined him a thin, little man with a bald head but here he was bearing the same hair and features as her first husband and my father. How odd, I thought – she simply repeated the make. For a short while, I felt an enormous anger climb into my being mixed with pity for my father who was obviously simply the last.

Because I possessed slim, long fingers, (pianist’s fingers, she claimed) she determined that I too should become a pianist and began the task of teach- ing me – to no avail. Despite my imaginings, the reality of the pianoforte bored me with its repetitions of scales, its study of theory and the banality of my first pieces. I was hopeless and did not enjoy it. My hands yearned to paint, to write poetry. My slim, long fingers, in later life, served me in becoming an artist. She had more success with my younger brother, Guus, who throughout his adult life, forged a sideline career as a jazz pianist, playing in restaurants and clubs.

www.fragmentsbyjosedekoster.com

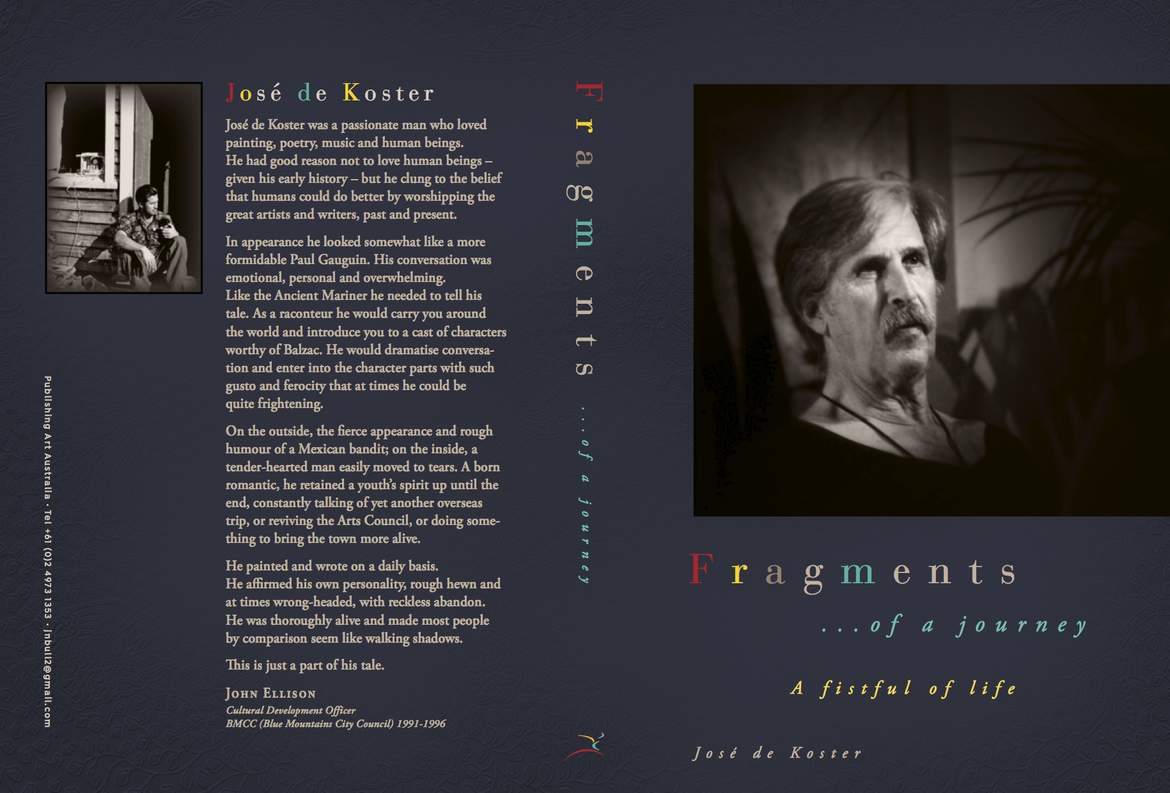

fragments of a Journey, A Fisful of Life

Jose de Koster

Jose de Koster

The Birds, by author, oil on canvas

My mother was large and solidly beautiful

Father w

Father was a planter, manager of a tobacco plantation owned by the Deli Maatschappij

The swimming pool was our second home

I see you seated in the cool of the piano room,

body swaying, fingers dancing on the ivory keys.

Outside, passing people pause,

dream of the past, the future.

Street vendors set up shop and sell their wares

in silence, listening to the Chopin magic.

I always listened somewhere alone.