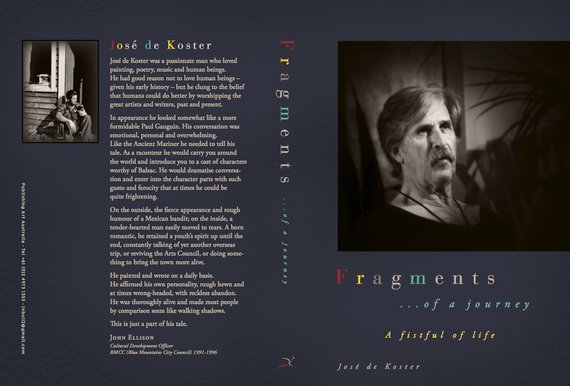

Fragments of a Journey

A Fistful of Life

www.fragmentsbyjosedekoster.com

Blog 10

Hi Everyone, A glorious spring day here in the mountains. here is the next instalment of the book. This one carries on from Blog 8 narrative-wise as Blog 9 contained merely some poems that were included in the book. happy reading! Tick like if you enjoyed what you have read.

Shortly after the Japanese arrived, internment camps began spring up in various areas. The first people to be sent there were Dutch adult males and especially those people who worked for the government in some capacity or other. My father, who by this time, had been pensioned of as an administrator of the Deli,took on a part time job teaching agriculture in the Agricultural College in Malang and therefore was an employee of the government. He was instructed to present himself with a bedroll and some clothes at the Fraterschool where the brother of the Franciscan order had taught and where I had attended for a short period before the Japanese came. He duly arrived and with many others, waited there patiently for the train to come and transport them to their destination. My father was sent to a camp called Kesilir, once a kind of kibbutz for Indos.

My younger brother, Guus, and I waited at the back of the house along the railway track, waiting for the train to rumble past. My father was already on the train having boarded at an earlier station near the school. Suddenly, we heard the tracks sing and we both yelled “ It's coming, Ed”. My elder brother was high up in a klengkeng tree on the platform, waiting for the train. He did not descend, however,as the razzias (rounding up of adult males) was in full swing and so, observed from his hiding post. As the train shuddered to a halt, we started to search the windows. “there!” and we found him, sitting with our cousin, (the son of my mother's brother), Eddy M. We ran and ran alongside the train which was slowly dragging itself away from the station, all the way till we reached the end of the platform, then down its slope which descended into the river, our faces wet

with tears and hearts amok with pain as we watched the train disappear towards Banjoewangi and then on to Kesilir.

We were allowed to visit him once in the beginning, brought him food and some items to make life easier as well as provisions for Eddy M and our uncle Guus whose wife and children moved to our house when he was taken away. Many years later, staying in The Netherlands with my eldest son, I suffered a heart attack and was visited in hospital by two of those children and discussed that period of time – when the world of our youth fell apart, the war dragged on and my father disappeared into the endless time.

When the last sounds of the departing train died into a silence,I made my way to a slokan (deep gutter) , behind the house of Oosthuis family, curled on the grass and wept piteously. I suddenly heard a voice behind me, shaking me out of my misery.

“kenapa nangis njo”. (Why are you crying?)

Hastily wiping my tears, I jumped up and spun around, my sadness giving way to adolescent anger at the shame of showing weakness, I yelled, “I am not crying. Who's crying”. I saw, in the creek, the solitary figure of a young woman staring at me quizzically, her beautiful face etched with a hint of cheekiness. “Sudah” (okay), she said and carried on bathing in the river, daring me to look and at the same time dismissing me. As in a trance, mesmerised, I watched her slowly and sinuously submerge her full body into the water. After a moment or two, she shot up, her sarong hugging her body tightly, accentuating her figure (Venus arising out of the waters), my young, sad heart became inflamed instantly and my father's train was not just a distant memory but for a little while, totally forgotten.

“What do you want”, she said,. “life is continuing, no?”

This was the young woman who had, on a wonderful day, ended the career of the Japanese sergeant whom we called Tatatitottettot. He would wait till midday, when the heat of the midday sun hung heavily in our limbs and all the world would go to their beds to try and sleep or just rest, when when only the animals, and sometimes not even they, would walk the earth. It was precisely at that time, that we would hear him, marching past accompanied with four or five trumpeters doing their best to create the utmost cacophany so that even sticking our heads under our pillows failed to mute the sound to enable us to sleep. His voice would snarl, “ tatatitottettot” continuously, on an on as he marched past. W boys would roll around restlessly, eventually getting up to sit on the cool, stone floor of the bedroom, cursing his tatatitottettot.

One fine day, she, my lady of the creek, wiggled her bottom past his prying eyes and shook her wet hair at him with a flirtatious smile. Looking back over her shoulder at him invitingly, she sashayed towards the village ; he, like a dog on hea, followed. Tatatittottettot! What exactly happened in the kampong, no-one knew and if they did, no-one said. Some time later, we saw him slink back past us and his cap slung low over his bashed-in face, his clothes all torn and no more tatatittottettott in his voice or his eyes told us the story which ended his career as teacher of the trumpet at ungodly times. He apparently had been placed somewhere else and to this day, I sometimes wonder, if he is still alive, whether he remembers the wiggle that cost him two black eyes and total loss of dignity. I know that I remember her, the siren of the creek, to this day in my yearning loins. For me, at thirteen years of age, she was not just a temptress of high calibre but a heroine of huge proportions, a Jeanne d'Arc who burned into my heart and blood.

Only once more, during those war years, did I see my father. My mother, my brother, Guus and I took the train to Kesilir hoping to see him even though we were told it might be a journey taken in vain. The train slowly rolled out of the station, taking us north then east through the sweltering,steamy day, made even more so as the carriage was filled with sweaty people hoping to see their imprisoned loved ones. We arrived at Benculuk which was the end of the rail and made our way to a large shed opposite the station where those hoping to visit the camp were temporarily housed until given permission to make their way to Kesilir and the camp. The shed, like the train, was steaming with the sweat-drenched multitude crowded shoulder to shoulder within. Drowsy with the heat and tired from the journey, I lay on the floor at the back of the shed to take a short nap, being very aware not to press too closely to the large woman lying next to me. When I awoke, and

on doing so, also roused her, I was mortified to find myself hugging her bottom – that of a complete stranger. I think she felt just as uncomfortable as I was. We slept very little that night. The adults chatted with friends, old and newly-formed while the youth in our shed escaped outside into the cool of the evening and sat under the waringin tree (weeping fig tree), talking, laughing, planning heroic feats and flirting with the opposite gender.

The following day, having been given permission to leave and visit, my mother hired a sado (a type of carriage) and trundled off, clippity-clopping, to the hut in front of the bridge at Kesilir where we were to identify ourselves before my father would be alerted to our coming. We were approached by a uniformed officer of the Japanese army. He was a mild-mannered, slender man with a long, thin face but what impressed me deeply was that this was the first time I had seen a uniformed officer who still had hair on his skull. His manner towards my mother was surprisingly courteous and not at all what I was expecting. I was told, I do not remember by whom, that before the war, he had been an economist.

Finally, we crossed the bridge over the muddy river and at the other end, we saw my father coming hesitantly towards us. We met up with many tears and hugs. I cuddled his leg and keenly felt the sense of loss which had permeated my being. We sat under the shade of a tree, and had a kind of picnic with food my mother had prepared and brought. My father was so unlike the man who had gone away;he was mostly silent and insecure, nervously and constantly looking around as if wary and on the alert for something unpleasant to happen. I do not remember much of that visit but still recall vividly the experience of going to the toilet. The toilet, I discovered, was merely a trench with a creek supposedly running through it but the trickle of water which did flow was not strong enough to push the faeces away. If anything, I think it was the liquid flow of multiple passings of urine which which played a greater part in moving them. I can still recall the terrible stench which burned my nostrils and churned my stomach.

In tears, we left our father, turning back constantly and waving to him on the other side of the bridge standing in the distance and reboarded the sado which took us back to Benculuk. This would be the last time that we saw him until several years later when he arrived in The Netherlands. After the war and having been released from his prison, he and my eldest brother made their way back to Malang and to the house which had been his home, he discovered that it was occupied by a family who had commandeered it. Before they had a chance to make any other arrangements, they found themselves picked up by the Pemudas (young guerilla fighters against the Dutch colonials) of the new Republic of Indonesia and locked in the Kleine Boeie, a small prison in Malang now housing Dutch colonials.

Back we arrived in Malang, hot, tired and happy to be together, Saidja and Rawi pressing us for details of our meeting with dad. The house was filled with relatives all wanting to know about conditions in the camp, Dad's health and well-being and general morale. We were now entering the next stage of fear,that of the camps. Before my father's internment, the fear we felt at the beginning of the Japanese occupation had eased itself into a state of resignation, something to put up with until the war ended. Now, however, the possibility of some or all of us (especially older brother, Ed) also being interned became a reality and my mother faced it with dread.

Our days often began with Ed and me, or sometimes just Ed alone,going to the pasar (market) near the station to purchase breakfast which on most occasions was pecil, a varie

Shortly after the Japanese arrived, internment camps began spring up in various areas. The first people to be sent there were Dutch adult males and especially those people who worked for the government in some capacity or other. My father, who by this time, had been pensioned of as an administrator of the Deli,took on a part time job teaching agriculture in the Agricultural College in Malang and therefore was an employee of the government. He was instructed to present himself with a bedroll and some clothes at the Fraterschool where the brother of the Franciscan order had taught and where I had attended for a short period before the Japanese came. He duly arrived and with many others, waited there patiently for the train to come and transport them to their destination. My father was sent to a camp called Kesilir, once a kind of kibbutz for Indos.

My younger brother, Guus, and I waited at the back of the house along the railway track, waiting for the train to rumble past. My father was already on the train having boarded at an earlier station near the school. Suddenly, we heard the tracks sing and we both yelled “ It's coming, Ed”. My elder brother was high up in a klengkeng tree on the platform, waiting for the train. He did not descend, however,as the razzias (rounding up of adult males) was in full swing and so, observed from his hiding post. As the train shuddered to a halt, we started to search the windows. “there!” and we found him, sitting with our cousin, (the son of my mother's brother), Eddy M. We ran and ran alongside the train which was slowly dragging itself away from the station, all the way till we reached the end of the platform, then down its slope which descended into the river, our faces wet

with tears and hearts amok with pain as we watched the train disappear towards Banjoewangi and then on to Kesilir.

We were allowed to visit him once in the beginning, brought him food and some items to make life easier as well as provisions for Eddy M and our uncle Guus whose wife and children moved to our house when he was taken away. Many years later, staying in The Netherlands with my eldest son, I suffered a heart attack and was visited in hospital by two of those children and discussed that period of time – when the world of our youth fell apart, the war dragged on and my father disappeared into the endless time.

When the last sounds of the departing train died into a silence,I made my way to a slokan (deep gutter) , behind the house of Oosthuis family, curled on the grass and wept piteously. I suddenly heard a voice behind me, shaking me out of my misery.

“kenapa nangis njo”. (Why are you crying?)

Hastily wiping my tears, I jumped up and spun around, my sadness giving way to adolescent anger at the shame of showing weakness, I yelled, “I am not crying. Who's crying”. I saw, in the creek, the solitary figure of a young woman staring at me quizzically, her beautiful face etched with a hint of cheekiness. “Sudah” (okay), she said and carried on bathing in the river, daring me to look and at the same time dismissing me. As in a trance, mesmerised, I watched her slowly and sinuously submerge her full body into the water. After a moment or two, she shot up, her sarong hugging her body tightly, accentuating her figure (Venus arising out of the waters), my young, sad heart became inflamed instantly and my father's train was not just a distant memory but for a little while, totally forgotten.

“What do you want”, she said,. “life is continuing, no?”

This was the young woman who had, on a wonderful day, ended the career of the Japanese sergeant whom we called Tatatitottettot. He would wait till midday, when the heat of the midday sun hung heavily in our limbs and all the world would go to their beds to try and sleep or just rest, when when only the animals, and sometimes not even they, would walk the earth. It was precisely at that time, that we would hear him, marching past accompanied with four or five trumpeters doing their best to create the utmost cacophany so that even sticking our heads under our pillows failed to mute the sound to enable us to sleep. His voice would snarl, “ tatatitottettot” continuously, on an on as he marched past. W boys would roll around restlessly, eventually getting up to sit on the cool, stone floor of the bedroom, cursing his tatatitottettot.

One fine day, she, my lady of the creek, wiggled her bottom past his prying eyes and shook her wet hair at him with a flirtatious smile. Looking back over her shoulder at him invitingly, she sashayed towards the village ; he, like a dog on hea, followed. Tatatittottettot! What exactly happened in the kampong, no-one knew and if they did, no-one said. Some time later, we saw him slink back past us and his cap slung low over his bashed-in face, his clothes all torn and no more tatatittottettott in his voice or his eyes told us the story which ended his career as teacher of the trumpet at ungodly times. He apparently had been placed somewhere else and to this day, I sometimes wonder, if he is still alive, whether he remembers the wiggle that cost him two black eyes and total loss of dignity. I know that I remember her, the siren of the creek, to this day in my yearning loins. For me, at thirteen years of age, she was not just a temptress of high calibre but a heroine of huge proportions, a Jeanne d'Arc who burned into my heart and blood.

Only once more, during those war years, did I see my father. My mother, my brother, Guus and I took the train to Kesilir hoping to see him even though we were told it might be a journey taken in vain. The train slowly rolled out of the station, taking us north then east through the sweltering,steamy day, made even more so as the carriage was filled with sweaty people hoping to see their imprisoned loved ones. We arrived at Benculuk which was the end of the rail and made our way to a large shed opposite the station where those hoping to visit the camp were temporarily housed until given permission to make their way to Kesilir and the camp. The shed, like the train, was steaming with the sweat-drenched multitude crowded shoulder to shoulder within. Drowsy with the heat and tired from the journey, I lay on the floor at the back of the shed to take a short nap, being very aware not to press too closely to the large woman lying next to me. When I awoke, and

on doing so, also roused her, I was mortified to find myself hugging her bottom – that of a complete stranger. I think she felt just as uncomfortable as I was. We slept very little that night. The adults chatted with friends, old and newly-formed while the youth in our shed escaped outside into the cool of the evening and sat under the waringin tree (weeping fig tree), talking, laughing, planning heroic feats and flirting with the opposite gender.

The following day, having been given permission to leave and visit, my mother hired a sado (a type of carriage) and trundled off, clippity-clopping, to the hut in front of the bridge at Kesilir where we were to identify ourselves before my father would be alerted to our coming. We were approached by a uniformed officer of the Japanese army. He was a mild-mannered, slender man with a long, thin face but what impressed me deeply was that this was the first time I had seen a uniformed officer who still had hair on his skull. His manner towards my mother was surprisingly courteous and not at all what I was expecting. I was told, I do not remember by whom, that before the war, he had been an economist.

Finally, we crossed the bridge over the muddy river and at the other end, we saw my father coming hesitantly towards us. We met up with many tears and hugs. I cuddled his leg and keenly felt the sense of loss which had permeated my being. We sat under the shade of a tree, and had a kind of picnic with food my mother had prepared and brought. My father was so unlike the man who had gone away;he was mostly silent and insecure, nervously and constantly looking around as if wary and on the alert for something unpleasant to happen. I do not remember much of that visit but still recall vividly the experience of going to the toilet. The toilet, I discovered, was merely a trench with a creek supposedly running through it but the trickle of water which did flow was not strong enough to push the faeces away. If anything, I think it was the liquid flow of multiple passings of urine which which played a greater part in moving them. I can still recall the terrible stench which burned my nostrils and churned my stomach.

In tears, we left our father, turning back constantly and waving to him on the other side of the bridge standing in the distance and reboarded the sado which took us back to Benculuk. This would be the last time that we saw him until several years later when he arrived in The Netherlands. After the war and having been released from his prison, he and my eldest brother made their way back to Malang and to the house which had been his home, he discovered that it was occupied by a family who had commandeered it. Before they had a chance to make any other arrangements, they found themselves picked up by the Pemudas (young guerilla fighters against the Dutch colonials) of the new Republic of Indonesia and locked in the Kleine Boeie, a small prison in Malang now housing Dutch colonials.

Back we arrived in Malang, hot, tired and happy to be together, Saidja and Rawi pressing us for details of our meeting with dad. The house was filled with relatives all wanting to know about conditions in the camp, Dad's health and well-being and general morale. We were now entering the next stage of fear,that of the camps. Before my father's internment, the fear we felt at the beginning of the Japanese occupation had eased itself into a state of resignation, something to put up with until the war ended. Now, however, the possibility of some or all of us (especially older brother, Ed) also being interned became a reality and my mother faced it with dread.

Our days often began with Ed and me, or sometimes just Ed alone,going to the pasar (market) near the station to purchase breakfast which on most occasions was pecil, a varie

Shortly after the Japanese arrived, internment camps began spring up in various areas. The first people to be sent there were Dutch adult males and especially those people who worked for the government in some capacity or other. My father, who by this time, had been pensioned of as an administrator of the Deli,took on a part time job teaching agriculture in the Agricultural College in Malang and therefore was an employee of the government. He was instructed to present himself with a bedroll and some clothes at the Fraterschool where the brother of the Franciscan order had taught and where I had attended for a short period before the Japanese came. He duly arrived and with many others, waited there patiently for the train to come and transport them to their destination. My father was sent to a camp called Kesilir, once a kind of kibbutz for Indos.

My younger brother, Guus, and I waited at the back of the house along the railway track, waiting for the train to rumble past. My father was already on the train having boarded at an earlier station near the school. Suddenly, we heard the tracks sing and we both yelled “ It's coming, Ed”. My elder brother was high up in a klengkeng tree on the platform, waiting for the train. He did not descend, however,as the razzias (rounding up of adult males) was in full swing and so, observed from his hiding post. As the train shuddered to a halt, we started to search the windows. “there!” and we found him, sitting with our cousin, (the son of my mother's brother), Eddy M. We ran and ran alongside the train which was slowly dragging itself away from the station, all the way till we reached the end of the platform, then down its slope which descended into the river, our faces wet

with tears and hearts amok with pain as we watched the train disappear towards Banjoewangi and then on to Kesilir.

We were allowed to visit him once in the beginning, brought him food and some items to make life easier as well as provisions for Eddy M and our uncle Guus whose wife and children moved to our house when he was taken away. Many years later, staying in The Netherlands with my eldest son, I suffered a heart attack and was visited in hospital by two of those children and discussed that period of time – when the world of our youth fell apart, the war dragged on and my father disappeared into the endless time.

When the last sounds of the departing train died into a silence,I made my way to a slokan (deep gutter) , behind the house of Oosthuis family, curled on the grass and wept piteously. I suddenly heard a voice behind me, shaking me out of my misery.

“kenapa nangis njo”. (Why are you crying?)

Hastily wiping my tears, I jumped up and spun around, my sadness giving way to adolescent anger at the shame of showing weakness, I yelled, “I am not crying. Who's crying”. I saw, in the creek, the solitary figure of a young woman staring at me quizzically, her beautiful face etched with a hint of cheekiness. “Sudah” (okay), she said and carried on bathing in the river, daring me to look and at the same time dismissing me. As in a trance, mesmerised, I watched her slowly and sinuously submerge her full body into the water. After a moment or two, she shot up, her sarong hugging her body tightly, accentuating her figure (Venus arising out of the waters), my young, sad heart became inflamed instantly and my father's train was not just a distant memory but for a little while, totally forgotten.

“What do you want”, she said,. “life is continuing, no?”

This was the young woman who had, on a wonderful day, ended the career of the Japanese sergeant whom we called Tatatitottettot. He would wait till midday, when the heat of the midday sun hung heavily in our limbs and all the world would go to their beds to try and sleep or just rest, when when only the animals, and sometimes not even they, would walk the earth. It was precisely at that time, that we would hear him, marching past accompanied with four or five trumpeters doing their best to create the utmost cacophany so that even sticking our heads under our pillows failed to mute the sound to enable us to sleep. His voice would snarl, “ tatatitottettot” continuously, on an on as he marched past. W boys would roll around restlessly, eventually getting up to sit on the cool, stone floor of the bedroom, cursing his tatatitottettot.

One fine day, she, my lady of the creek, wiggled her bottom past his prying eyes and shook her wet hair at him with a flirtatious smile. Looking back over her shoulder at him invitingly, she sashayed towards the village ; he, like a dog on hea, followed. Tatatittottettot! What exactly happened in the kampong, no-one knew and if they did, no-one said. Some time later, we saw him slink back past us and his cap slung low over his bashed-in face, his clothes all torn and no more tatatittottettott in his voice or his eyes told us the story which ended his career as teacher of the trumpet at ungodly times. He apparently had been placed somewhere else and to this day, I sometimes wonder, if he is still alive, whether he remembers the wiggle that cost him two black eyes and total loss of dignity. I know that I remember her, the siren of the creek, to this day in my yearning loins. For me, at thirteen years of age, she was not just a temptress of high calibre but a heroine of huge proportions, a Jeanne d'Arc who burned into my heart and blood.

Only once more, during those war years, did I see my father. My mother, my brother, Guus and I took the train to Kesilir hoping to see him even though we were told it might be a journey taken in vain. The train slowly rolled out of the station, taking us north then east through the sweltering,steamy day, made even more so as the carriage was filled with sweaty people hoping to see their imprisoned loved ones. We arrived at Benculuk which was the end of the rail and made our way to a large shed opposite the station where those hoping to visit the camp were temporarily housed until given permission to make their way to Kesilir and the camp. The shed, like the train, was steaming with the sweat-drenched multitude crowded shoulder to shoulder within. Drowsy with the heat and tired from the journey, I lay on the floor at the back of the shed to take a short nap, being very aware not to press too closely to the large woman lying next to me. When I awoke, and

on doing so, also roused her, I was mortified to find myself hugging her bottom – that of a complete stranger. I think she felt just as uncomfortable as I was. We slept very little that night. The adults chatted with friends, old and newly-formed while the youth in our shed escaped outside into the cool of the evening and sat under the waringin tree (weeping fig tree), talking, laughing, planning heroic feats and flirting with the opposite gender.

The following day, having been given permission to leave and visit, my mother hired a sado (a type of carriage) and trundled off, clippity-clopping, to the hut in front of the bridge at Kesilir where we were to identify ourselves before my father would be alerted to our coming. We were approached by a uniformed officer of the Japanese army. He was a mild-mannered, slender man with a long, thin face but what impressed me deeply was that this was the first time I had seen a uniformed officer who still had hair on his skull. His manner towards my mother was surprisingly courteous and not at all what I was expecting. I was told, I do not remember by whom, that before the war, he had been an economist.

Finally, we crossed the bridge over the muddy river and at the other end, we saw my father coming hesitantly towards us. We met up with many tears and hugs. I cuddled his leg and keenly felt the sense of loss which had permeated my being. We sat under the shade of a tree, and had a kind of picnic with food my mother had prepared and brought. My father was so unlike the man who had gone away;he was mostly silent and insecure, nervously and constantly looking around as if wary and on the alert for something unpleasant to happen. I do not remember much of that visit but still recall vividly the experience of going to the toilet. The toilet, I discovered, was merely a trench with a creek supposedly running through it but the trickle of water which did flow was not strong enough to push the faeces away. If anything, I think it was the liquid flow of multiple passings of urine which which played a greater part in moving them. I can still recall the terrible stench which burned my nostrils and churned my stomach.

In tears, we left our father, turning back constantly and waving to him on the other side of the bridge standing in the distance and reboarded the sado which took us back to Benculuk. This would be the last time that we saw him until several years later when he arrived in The Netherlands. After the war and having been released from his prison, he and my eldest brother made their way back to Malang and to the house which had been his home, he discovered that it was occupied by a family who had commandeered it. Before they had a chance to make any other arrangements, they found themselves picked up by the Pemudas (young guerilla fighters against the Dutch colonials) of the new Republic of Indonesia and locked in the Kleine Boeie, a small prison in Malang now housing Dutch colonials.

Back we arrived in Malang, hot, tired and happy to be together, Saidja and Rawi pressing us for details of our meeting with dad. The house was filled with relatives all wanting to know about conditions in the camp, Dad's health and well-being and general morale. We were now entering the next stage of fear,that of the camps. Before my father's internment, the fear we felt at the beginning of the Japanese occupation had eased itself into a state of resignation, something to put up with until the war ended. Now, however, the possibility of some or all of us (especially older brother, Ed) also being interned became a reality and my mother faced it with dread.

Our days often began with Ed and me, or sometimes just Ed alone,going to the pasar (market) near the station to purchase breakfast which on most occasions was pecil, a varie

Shortly after the Japanese arrived, internment camps began spring up in various areas. The first people to be sent there were Dutch adult males and especially those people who worked for the government in some capacity or other. My father, who by this time, had been pensioned of as an administrator of the Deli,took on a part time job teaching agriculture in the Agricultural College in Malang and therefore was an employee of the government. He was instructed to present himself with a bedroll and some clothes at the Fraterschool where the brother of the Franciscan order had taught and where I had attended for a short period before the Japanese came. He duly arrived and with many others, waited there patiently for the train to come and transport them to their destination. My father was sent to a camp called Kesilir, once a kind of kibbutz for Indos.

My younger brother, Guus, and I waited at the back of the house along the railway track, waiting for the train to rumble past. My father was already on the train having boarded at an earlier station near the school. Suddenly, we heard the tracks sing and we both yelled “ It's coming, Ed”. My elder brother was high up in a klengkeng tree on the platform, waiting for the train. He did not descend, however,as the razzias (rounding up of adult males) was in full swing and so, observed from his hiding post. As the train shuddered to a halt, we started to search the windows. “there!” and we found him, sitting with our cousin, (the son of my mother's brother), Eddy M. We ran and ran alongside the train which was slowly dragging itself away from the station, all the way till we reached the end of the platform, then down its slope which descended into the river, our faces wet

with tears and hearts amok with pain as we watched the train disappear towards Banjoewangi and then on to Kesilir.

We were allowed to visit him once in the beginning, brought him food and some items to make life easier as well as provisions for Eddy M and our uncle Guus whose wife and children moved to our house when he was taken away. Many years later, staying in The Netherlands with my eldest son, I suffered a heart attack and was visited in hospital by two of those children and discussed that period of time – when the world of our youth fell apart, the war dragged on and my father disappeared into the endless time.

When the last sounds of the departing train died into a silence,I made my way to a slokan (deep gutter) , behind the house of Oosthuis family, curled on the grass and wept piteously. I suddenly heard a voice behind me, shaking me out of my misery.

“kenapa nangis njo”. (Why are you crying?)

Hastily wiping my tears, I jumped up and spun around, my sadness giving way to adolescent anger at the shame of showing weakness, I yelled, “I am not crying. Who's crying”. I saw, in the creek, the solitary figure of a young woman staring at me quizzically, her beautiful face etched with a hint of cheekiness. “Sudah” (okay), she said and carried on bathing in the river, daring me to look and at the same time dismissing me. As in a trance, mesmerised, I watched her slowly and sinuously submerge her full body into the water. After a moment or two, she shot up, her sarong hugging her body tightly, accentuating her figure (Venus arising out of the waters), my young, sad heart became inflamed instantly and my father's train was not just a distant memory but for a little while, totally forgotten.

“What do you want”, she said,. “life is continuing, no?”

This was the young woman who had, on a wonderful day, ended the career of the Japanese sergeant whom we called Tatatitottettot. He would wait till midday, when the heat of the midday sun hung heavily in our limbs and all the world would go to their beds to try and sleep or just rest, when when only the animals, and sometimes not even they, would walk the earth. It was precisely at that time, that we would hear him, marching past accompanied with four or five trumpeters doing their best to create the utmost cacophany so that even sticking our heads under our pillows failed to mute the sound to enable us to sleep. His voice would snarl, “ tatatitottettot” continuously, on an on as he marched past. W boys would roll around restlessly, eventually getting up to sit on the cool, stone floor of the bedroom, cursing his tatatitottettot.

One fine day, she, my lady of the creek, wiggled her bottom past his prying eyes and shook her wet hair at him with a flirtatious smile. Looking back over her shoulder at him invitingly, she sashayed towards the village ; he, like a dog on hea, followed. Tatatittottettot! What exactly happened in the kampong, no-one knew and if they did, no-one said. Some time later, we saw him slink back past us and his cap slung low over his bashed-in face, his clothes all torn and no more tatatittottettott in his voice or his eyes told us the story which ended his career as teacher of the trumpet at ungodly times. He apparently had been placed somewhere else and to this day, I sometimes wonder, if he is still alive, whether he remembers the wiggle that cost him two black eyes and total loss of dignity. I know that I remember her, the siren of the creek, to this day in my yearning loins. For me, at thirteen years of age, she was not just a temptress of high calibre but a heroine of huge proportions, a Jeanne d'Arc who burned into my heart and blood.

Only once more, during those war years, did I see my father. My mother, my brother, Guus and I took the train to Kesilir hoping to see him even though we were told it might be a journey taken in vain. The train slowly rolled out of the station, taking us north then east through the sweltering,steamy day, made even more so as the carriage was filled with sweaty people hoping to see their imprisoned loved ones. We arrived at Benculuk which was the end of the rail and made our way to a large shed opposite the station where those hoping to visit the camp were temporarily housed until given permission to make their way to Kesilir and the camp. The shed, like the train, was steaming with the sweat-drenched multitude crowded shoulder to shoulder within. Drowsy with the heat and tired from the journey, I lay on the floor at the back of the shed to take a short nap, being very aware not to press too closely to the large woman lying next to me. When I awoke, and

on doing so, also roused her, I was mortified to find myself hugging her bottom – that of a complete stranger. I think she felt just as uncomfortable as I was. We slept very little that night. The adults chatted with friends, old and newly-formed while the youth in our shed escaped outside into the cool of the evening and sat under the waringin tree (weeping fig tree), talking, laughing, planning heroic feats and flirting with the opposite gender.

The following day, having been given permission to leave and visit, my mother hired a sado (a type of carriage) and trundled off, clippity-clopping, to the hut in front of the bridge at Kesilir where we were to identify ourselves before my father would be alerted to our coming. We were approached by a uniformed officer of the Japanese army. He was a mild-mannered, slender man with a long, thin face but what impressed me deeply was that this was the first time I had seen a uniformed officer who still had hair on his skull. His manner towards my mother was surprisingly courteous and not at all what I was expecting. I was told, I do not remember by whom, that before the war, he had been an economist.

Finally, we crossed the bridge over the muddy river and at the other end, we saw my father coming hesitantly towards us. We met up with many tears and hugs. I cuddled his leg and keenly felt the sense of loss which had permeated my being. We sat under the shade of a tree, and had a kind of picnic with food my mother had prepared and brought. My father was so unlike the man who had gone away;he was mostly silent and insecure, nervously and constantly looking around as if wary and on the alert for something unpleasant to happen. I do not remember much of that visit but still recall vividly the experience of going to the toilet. The toilet, I discovered, was merely a trench with a creek supposedly running through it but the trickle of water which did flow was not strong enough to push the faeces away. If anything, I think it was the liquid flow of multiple passings of urine which which played a greater part in moving them. I can still recall the terrible stench which burned my nostrils and churned my stomach.

In tears, we left our father, turning back constantly and waving to him on the other side of the bridge standing in the distance and reboarded the sado which took us back to Benculuk. This would be the last time that we saw him until several years later when he arrived in The Netherlands. After the war and having been released from his prison, he and my eldest brother made their way back to Malang and to the house which had been his home, he discovered that it was occupied by a family who had commandeered it. Before they had a chance to make any other arrangements, they found themselves picked up by the Pemudas (young guerilla fighters against the Dutch colonials) of the new Republic of Indonesia and locked in the Kleine Boeie, a small prison in Malang now housing Dutch colonials.

Back we arrived in Malang, hot, tired and happy to be together, Saidja and Rawi pressing us for details of our meeting with dad. The house was filled with relatives all wanting to know about conditions in the camp, Dad's health and well-being and general morale. We were now entering the next stage of fear,that of the camps. Before my father's internment, the fear we felt at the beginning of the Japanese occupation had eased itself into a state of resignation, something to put up with until the war ended. Now, however, the possibility of some or all of us (especially older brother, Ed) also being interned became a reality and my mother faced it with dread,