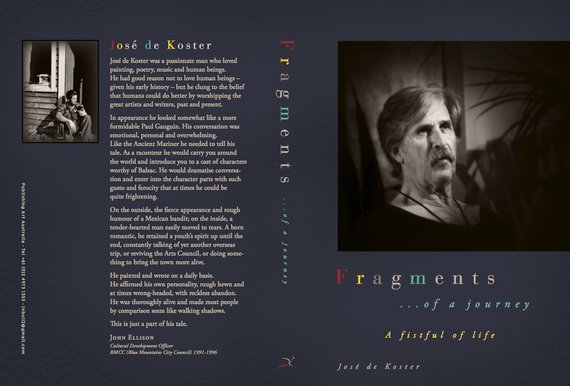

Fragments of a Journey

A Fistful of Life

www.fragmentsbyjosedekoster.com

Blog4

Many, many apologies to the readers following this blog for the enormous interval between this and the last one. I have been overseas for the last eight weeks with a new tablet from which I was unable, whether because of my ignorance or the machine playing up, to access the contents of m desktop (with the exception of email and facebook. Hence the delay. Because of such a long absence, I will include in this blog, more than I usually do. Happy reading!

My maternal grandfather was the opposite to me, known as “the tiger killer of Java”. He would make traps, deep holes dug deep with bamboo stakes,pointing upwards into which a bit of goat meat was lowered, the smell of which would lure the hungry tiger to fall in and be impaled by the bamboo spears.

Tani later exerted the same calming influence when my younger brother, Guus, and I spotted two pythons in alongparrit, a deep trench built to allow the water to escape in those heavy tropical rains. Filled with fear, we ran screaming back into the house and were caught in the arms of Tani who carried us back to where the snakes were and showed us that they were sleeping and not to be feared. “ When you sleep, who fears you? No-one should. It is the same with them,” he explained. Later, when we shifted our domicile to the city Medan, I asked my father why he had brought two python skins to hang on the wall of his study.

“Well,” he answered, “those were the two that scared you and Guus on the plantation. Remember?”

I did indeed and to this day, feel weirdly guilty for having allowed my fear to kill those two. The tiger skin in my mother's piano room, it too, asked me to explain. Often I would get under it and pretend to be a tiger, trying to scare my brother. He did notscarehowever, merely kicked the skin and I would roll out from under.

Another sound which stays with me tothisday, is the haunting, wild cry of the siamang, (gibbon) which makes its sound by pursing its mouth into a funnel. Often, it caught me unawares and with fear, I would run straight into the tani's waiting arms and onto his shoulders where safety was assured.

On the same plantation where the pythons scared us,Toentoengan plantation,we had a swimming pool. It was actually a small river which had been blocked off at some fifty metres intervals, roughly concreted with a few steps leading into it. My mother went in one day and almost immediately let out a scream and bolted out. We soon saw the reason for her dismay. A small crocodile, was silently shifting through the waters, weaving this way and that, thoroughly enjoying itself. We never swam there again.

During that early period, I remember we had two dogs,dobermans named Tommy and Moppie – black, swift fires of anger, although in our presence, they were simply pussycats. The servants feared them despite the dogs sleeping in their quarters. One day, Tommy, who was a crazy fighter, engaged in a duel with a wild pig on the road in front of our house, a road which was no more than a clearing cut through the jungle some years previously and which saw only the occasional car and a few slow-moving grobaks scattering loose gravel. His guts hung half out of his body yet he tenaciously clung to the throat of the screaming pig until it died. Poor Tommy survived that fight. We had him stitched up by a dukun who swore all the time that no-one should have a dog which fought like a 'setan' (devil). The pig became dinner, thin slices of wild pig dried on the roof of the servants' quarters in preparation for dengeng, a delicacy which still makes my mouth water and is one of those yearnings which runs in the blood of the exile. Tommy's escape from an almost certain death on that occasion proved to be only a brief postponement.

One weekend, (it must have been a weekend because my father was home and away from the plantation), Tommy had gone missing early in the morning. My father and a small posse which included my older brother and me, went looking for him in the jungle, calling his name continuously. As we descended a slippery path into a kampong (village settlement), we heard barking, ferocious yet carrying within that ferocity, the hint of whining. We found Tommy, tied to a post, almost hidden amongst a cluster of small bamboo houses. There he was minus a leg, black tar smeared over where once a leg had been ( to stop the bleeding, no doubt). The Bataks were dog eaters - in Balige dog meat was sold openly in the markets – and poor Tommy was stolen and destined to be eaten, piece by piece. We hurriedly untied him and made our way through the jungle back to our house. Poor Tommy, however, weakened and perhaps infected by the amputation, did not survive the journey. I remember blood slowly trickling from his mouth, his eyes rolling backwards, his body convulsing – and then nothing, just total stillness. I had witnessed my first death, the departing of the soul. I burst into a torrent of tears, tears not of pity or love, but of pure and total rage, anger at the God who could allow this to happen, anger at us humans who claimed an intelligence superior to animal intelligence but yet nearly always betrayed ourselves.

I cannot remember what happened to Moppie nor to her brood of puppies which roamed yelping intheback yard. One day, they were all gone and the memory for the reasons of their disappearance did not store them, just the black spots of sound.

Fragment : A dichotomy of faiths. I was brought up in my mother's faith. She was Roman Catholic and deeply devout unlike my father who had no interest in his Lutheran background. While the dogma and rituals of Catholicism were pounded into me as a child, they did not carry the same weight as the mystical, superstitious spiritualism of my babu, Musinem. Even my mother, born and raised in the atmosphere of her babu's influence, incorporated it into her being. We children feared less the wrath of an angry Catholic God than the appearance of the mommohs, invisible ancestral spirits whose presence can be felt and may come to do good or wreak destruction and havoc and whose presence we had to fight. Everywhere they lurk and target especially women and children, both of whom wallow in their deep mystery.The East was, and probably still is, awash with the fear of mommohs.

At one time in my childhood, I was sick with fever. My mother was singing Nina Bobo, a lullaby every child in the East knows, a song left over from Portuguese business dealings on these coasts. I remember my sudden scream. It cut itself out of my mouth, made my lips vibrate and thesweatpour out of my body. My mother held me tight against herself and Musinem gently caressed my forehead. I had seen a mommoh with the eyes of my grandfather in his skull. He had haunted me for years previously and after my illness until one night, Ed, my brother hit the mommoh with a weapon, a huge wooden stick which he bashed against the wall.He let the mommoh have it again and again even though the only result appeared to be a crack in the wall over the bed.But then, mommohs are invisible at the best of times. We found a dead gecko under the bed, flat and very visible but didn't want to admit what we both thought for fear of mocking the spirits and incurring vengeance, that we had killed a mommoh.

When my screaming did not subside,Musinem, still caressing me, yelled, “Setan pergi” (Satan, go away) then she disappeared, coming back shortly with the saviour of all children when the devil wanders through their soul, chicken broth.When I woke up the next day, still extremely tired and feverish,I knew, nevertheless, that my slim fight with death had been won by the three of us.The next day, Musinem came to my bedside, laid a hand on my forehead and suddeny all the devils left. Just like that. Fever stilled, headache gone, eyes clear – just like that ,hand on head. My mother told me that she herself laid her hand on my head to calm me down whenever I was angry. “All was gone. No anger. It is the sign of the Lord,” she explained. Not till later did I query this. How come, I asked my mother did Musinem who is Muslim have the same Lord as she did in achieving the same result with her hand on my head. She replied,”Your head is the seat of the Lord, your Lord.It is where your Lord and I or Musinem meet. Do you understand?”

Despite my mother's fervent Catholicism, as a child of the East, she also embraced, if perhaps subconsciously, the mysticism and magic of the East and listening to her, I discovered her God changed face many times, absorbing elements of her gurus, people likeGhandi, Krishnamurti, Gurdjev, Madame Blavatski, Jesus and especially, her father, Sam.

Musinem and my mother both had forceful eyes. Musinem had brown eyes with yellow flecks like a tiger, soft and gentle when she was with us, brooding and dangerous like a tiger on the prowl when she thought we needed protecting. My mother had black, imperious eyes, eyes that still frightened even in Ruysdaelstraat in Holland where she returned after the war, her body racked and ruined after the camp.She would sit in her chair like a queen on her throne, waiting.

My maternal grandmother, living in the Western civilisation of Den Bosch after the war, that tiny woman who could be as coquettish as any French mademoiselle, flirting her way into your eyes, heart and soul, carried with her the echoes of her past.”You areamonyet (a monkey), like those who dance and frolic near tombstones,” she said to me, pinching my bottom.When I asked my mother what she had meant about me being a monkey dancing near tombstones, my mother replied that it meant I had soul that my inner being dared to show itself. She told me not to be perturbed.

My grandmother was never old. She just died.Musinem disappeared from my life suddenly after we came back from a holiday in Holland. She is still here, however, has been all along, in my heart, in one of the many chambers in which love hides.