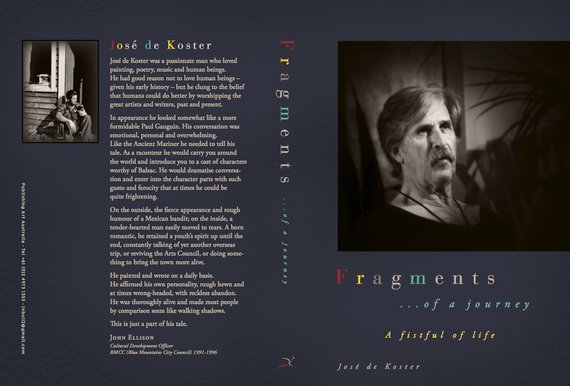

Fragments of a Journey

A Fistful of Life

www.fragmentsbyjosedekoster.com

Blog 5

A day of flooding rains, catastrophic fires and fierce windstorms. Hello Australia

A perfect day for staing indoors and reading the next instalment. Enjoy!

The house I remember best is the third house in the Laboratorium Weg which was opposite a deer park. It had a long circular drive which went past the house and onto the pendopo on the side (a pavilion-like structure supported by columns open on all sides affording cool shelter from the sun and protection from the rain.) in which sat rattan chairs and table where my parents would relax or entertain.The drive was lined with huge, old tjemarahs with massive roots spreading in all directions. Here, I would play with my men, clay figures I had made myself or little tin soldiers given to me by my family or their friends. They did not fight the great battles with cannons that other children created in their games. Mine wandered like ghosts through forests, speaking to the animals and living in peace.

The back garden was enormous and housed a chicken coop to the side and behind the house the kaki lima (pavement) led to the kitchen and the servants' living quarters. At the back of their area was a hedge and behind that stood a well in front of the servants' bathroom. It was in that hedge that I hid my valuables – cars, soldiers, marbles etc – till one day, I discovered that they had all disappeared, gone forever. I moped about the house for many a day after that, mourning their loss, lying often under the tiger skin in my mother's piano room, searching for comfort and the tiger's strength. Geese roamed free in the garden and scared not only visitors but often us kids and the servants themselves. We often saw miyawaks, huge lizards, some growing to two metres in length. They would roam the back yard trying to steal the chickens but were usually thwarted in their attempts as the geese scared them out of the yard. Miyawaks did not scare us. We would often swim in the river which ran at the back of the house with them. Only once did I feel intimidated. I had inadvertently got very close to one and did not notice it until the stench of his skin alerted me to its presence. I stopped and we both stared at each other, his beady eyes directing thoughts into my head. I slowly backed away and after some considerable distance, I turned and walked away quickly, my imagination running haywire with all sorts of improbable occurrences but nothing happened. The miyawak stood there unmoving. Miyawaks kill prey and are also scavengers, preferring to eat cadavers after they have well and truly rotted.I once found a dead dog, an alsatian, in the reeds lining the back of the jungle patch behind our house. The reptiles had hidden it there to work into edible bits. My brother, Ed and I used to watch them from the tree house he had built in the bough of a tree by the river. We would look down and see them cavorting in the muddy waters, dragging food – dead chooks, cats, dogs etc) - into their bamboo homes where it was left and eaten only when necessary. No gorging here. From our vantage point, we would look down on the kampong and observe people going about their daily business. We would watch women go to the river and do their washing by hitting the clothes on the beautiful river stones, huge boulders spewed out many, many centuries ago by either Sibayak or Sinabung, the twin mountains just beyond the edge of Medan.

Plantation life for me was a long day and night filled with joyous moments and love. Apart from my parents, the two people whom I loved most and who exerted the most influence were the aforementioned Tani and my nurse, Musinem. Tani would calm my fears by explaining them away while Musinem would soothe them away, by holding me close to her bosom, murmuring soft words of love. Her arms were like medicine, curing me of fear, of sadness, healing my childhood pains from the many scrapes in which I often found myself. Life consisted of us kids playing in huge gardens in groups or alone amongst the massive trees and watching out for semut appi, little red ants which would climb one's legs and sting a million bites a second. I hated those little bastards. Big ants – they could be spotted – but these little firebrands haunted me because they were unseen until they were felt. My early days were spent playing in the sand with little home-made toys and marbles. which, in my imagination, were transformed into soldiers of massive armies which roamed in my silent head. In our house I was a quiet child. My mother described me to everyone as “still waters”.

“ He never draws attention to himself – says nothing but just watches you” she would tell people. I was her “worry child” she would often proclaim.

My mother was a very large woman. I do not remember her ever being thin except for years later when the war had signalled its end and I staggered to the women's internment camp and saw her framed in a door, a skeleton weighing only 28 kilograms. When she saw me, she held out her arms, her dark eyes brimming with love and joyously, I ran into them. We didn't speak, just clung to each other whilst behind her, stood my younger brother who had managed to get to her earlier. (He and I had been in a camp about an hour's walk distance and only with the end of the war could we stagger to each other. ) But I digress! She was large and solidly beautiful and I still, to this day, some fifty years later, am embraced by the warmth of her being. She had moulded her family of five into a solid unit who knew everything about each other and who had fierce loyalties towards each other.

First School

Sitting at the deathbed of my older brother, Ed, his body ravaged by the cancer eating away at him, we reminisced about the long distant past and chortled about the antics of youth, and in particular, of one little five year old boy standing on his bed and pissing on the floor beside it. Comical in retrospect, it was less so at the time of the event as it was the first act of defiance by a deeply unhappy boy who could not understand why his world of love, security and his beloved jungle was so suddenly wrested from him. It was decided when I turned eight I should begin my academic education. Because of the isolation of the plantation, I was sent to join my brother at a boarding school run by the Jesuit Brothers in Berastagi (Brastagi in our old memory). It was here that the innate silence within me flourished. Now however, it was a silence born out of anger, a defence of the mind and the soul. It was here too, that the first seeds of rebellion were planted and gave sprout. I disliked the uniform, disliked the dinners and especially disliked the teacher who sat next to me at the head of the table. So many time, his ruler would come crashing over my fingers, those fingers so thin but which I instinctively already knew would become the implements that would tell the world, through my art, about my soul. Whack! The ruler descended whilst he lectured me on how to eat.

“You chew your food! Do not swallow until it has been chewed many, many times!” he would thunder.

And another whack for good measure. There were times I defied him by glaring arrogantly ( his word) at him, saying nothing. At those times, I would be banished to a table where I sat alone or with other malcontents (as it was put), the naughty people's table where at times, I forced to wear a pointed dunce's hat which he had fashioned for me, scarring my dignity beyond repair. “EAT!” he thundered and my secret heart told me to remember. That cap is imprinted on my memory as a symbol of misery. Later on, when, in the cinema, I saw KKK clansmen riding over the silver screen pursuing my heroes, my dislike for uniform grew and well before I knew the ethos of the KKK, I disliked them because of their uniform. Uniform clothing, uniform behaviour, uniform (and usually dogmatic) beliefs.

My parents would occasionally would send small parcels of food, little treats for my brother and me. These were placed in the kitchen's refrigerator, sometimes doled out to us but just as often not at all as they had somehow “disappeared”. My eyes turn in to the screen of memory seeing two boys, one five, one eight, sneaking out at night, raiding the fridge ( later it was padlocked) for our treats before they disappeared and eating in silence the delicious toentoengan cakes our cook had made.

Often, and hence the padlock, I suppose, we would be caught and thus copped many a caning.

The hollowness of my little boy's heart, the overwhelming misery of homesickness and my brother's refusal to act on my suggestion that we run away together gave birth to my first acts of rebellion and resistance – firstly, to piss on the floor each night, refuse to clean it up and cop the consequent caning and when that failed to cause my parents to take me home then refusing to eat (yes, Mum,your stories about Gandhi found root in me) which landed me in the school infirmary, weakened and with damaged kidneys. I remember the shrill screech of the teacher in charge of the infirmary screaming hysterically that “godverdomme” (a Dutch swear word) this had to stop and smacking me in a bid to make me eat. Silent warrior I was – no tears, no words, just a stance. Like Luther, I could not recant. Our parents were finally notified when I was in hospital and the male native nurse there told my mother in Javanese that this child should go home. “ Doroh, diya sakkit attibuat ibu-bapak.” My mother simply took me in her arms and said, “It is over now. We are going home.” My father, rather perplexed by that sudden decision, angrily demanded to know what would happen to the children's education now. My mother quietly and calmly told him that she would resume teaching the children and that they would go to school when he retired and shifted to the city.

Defiant Ed and his little brother, awakened by the life returned into the two, came home, sharing

our so-longed-for homecoming with a little baby brother, Guus, now a blond child running on his short legs. The laughter and joy so penetrated the jungle that somewhere a tiger spoke “Harimauuuuuau”. No more getting beaten, no more uniform. (To this day, no uniform has ever attracted me. I detest the stamp it puts on you. ) My heart was ready to burst with happiness at once again

I still have the maps of the plantation of the Deli My. Nowadays it is simply incorporated into Medan as suburbs and somehow I do not feel attracted to going back to revisit the place. Millions of people noisily crowding the streets where once inhabited silence.

Our homecoming, so joyful for me, extracted a heavy price from my father. He was forced to move closer to civilization so we three children could attend day school. To that end, he applied for a transfer to head office and secured a job in an administrative capacity, leaving behind his beloved jungle. His heart must have contracted with anger and loneliness for he was happy only amongst the tobacco and the huge sky which spoke of freedom. The longing for that life in the plantation stayed with my father till the day he died.