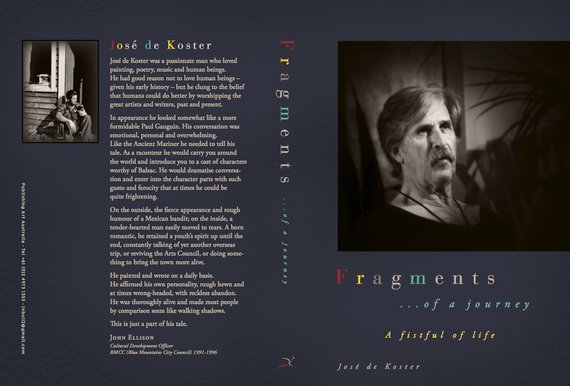

Fragments of a Journey

A Fisful of Life

www.fragmentsbyjosedekoster.com

Blog 7

Hope everyone had a lovely Christmas and a new year which began with promises of good things to come - comfort for bereaved people, peace of mind for the unhappy and the anxious, good fortune for those that need it. Here is the next instalment of the autobiography

In Malang, my father's place of work was confined to the four walls of a room instead of the wide spaces of the plantation that he so loved. I remember going to visit him in his office, an airy spacious room in the middle of which was an enormous, dark-brown mahogany two-sided desk on which sat several rows of pencils, all equally sharp-pointed, brought to that sharpness by the old Malay, the maintenance man whose job it was to ensure all pencils sharpened. His appearance remains vivid in my memory – thin, dark-brown chiselled face, long,elegant fingers, a pitji on his skull, the headdress preferred by the first president of Indonesia, bapak Karno (President Soekarno). At my new school, our pencils would also be sharpened by just such a man. He would take from us, the proffered pencils and without a word, began his business, placing each finished pencil on the ground in front of him, the pointed end facing the student. We did not pick them up until they were all finished then he would look into our eyes and react to our facial expressions. My tight, dark looks elicited a wide, spreading smile from him.

Fragment 1.

Someone sent me a postcard a few days ago. The postcard tells the story of a building, white, Dutch Empire style, heavy and solid like the burgers of Holland. On this postcard, however, were none of the trees that had stood there when Joost was a child. In particular, there was one tree to the right of the structure which wound itself around the building. It was in this tree that the child Joost would hide on one of its massive branches lying in its bough, snug and comfortable as any bed, perfect for observing the world and day-dreaming.

He would watch his father's window through which he could see him sitting at his immaculate desk with, on the right hand side, lay seven pencils with seven sharp points, which were sharpened seven times a day. Why seven, he wondered. Was it a mystical number? (Many years later in life, he had watched a Hollywood film called “The Seven Samurai” and the image of those pencils, sitting side by side like soldiers at the ready, returned to him).

One day, he saw a tall, white-haired, broad-shouldered man standing in front of his father. The man was speaking and my father appeared angry, tapping and gesticulating with one of the pencils, the sharp point directed toward the speaker. The boy slid down the tree, ran into the building through the side door, up the wide staircase and stood outside his father's door, the better to hear the conversation. He had only been there a few moments when suddenly the door was flung open throwing him backwards onto the floor. Both men bent down to pick him up and whilst their voices were solicitous, he could see in their eyes and faces, the ferocity of their silent conversation.

When the man left, the father guided Joost roughly to his office, pushed him into a chair and sat on a seat next to him. Through the window, Joost could see the tree he had recently vacated.

“Now listen to me! I do not want you to come to this office ever again. You understand? Never! Why are you crying?”

Joost could not answer. He was choking on his words, a consequence of crying, of shame, of embarrassment and fear. He sensed his father's eyes boring into him and for quite some time , neither spoke, both immobile, holding their respective positions.father and son and the mystery which is in between. Joost was a thin boy, supple and athletic with a dreamer's silence writ on his face. His father was a dark-haired, six-footer with a large nose and small eyes which he would squint to hide his thoughts. The boy never really understood him, his motives, his movements.They never held any long conversations, never did anything together, never confided in each other. The father held his own consultations at all times: he was simply the tuan basar (the boss)

“I was watching you and the man, pap, and I got worried”

“Watching us. What do you mean watching us? From where? Are you spying on me?”

“No, pap.I sometimes sit in that tree, that big one. I just sit there, that's all and I saw you. I am not spying, just looking. I like sitting there. It is my home away from home, my dream home.”

“Well, just let me catch you their again! I do not want to be spied on, you hear me?” Joost left the room quietly although in his heart, he raged. God is a bastard, he thought. Much of his comprehension of the world, of its people and of himself was explained with reference to that beloved God, instilled into his being by his devoutly Catholic mother. But already within the boy's heart, rebellion had taken root for, try as he might, he could not reconcile this mysterious, aloof and remote Being with the loving Father of his mother's God. Was not God perhaps, the beautiful music his mother played on her large Bechstein grand piano - Mozart's Piano Concerto,No21,K467,in particular the second movement, or the same movement of Beethoven's Piano Concerto, No5. It was then, he would hear the sound of God-like majesty and connect with the Supreme Being.He was in the music of his mother. Only a few years later, he totally forsook the religion of his mother. Out of deference to her, not wishing to disappoint her, he maintained the outward observances until the time of their internment.

He lied to her about his confessions. For quite some time, he would recite, in the confessional, a rehearsed litany of sins which he had supposedly committed. One day, quite exasperated by the behaviour of her two eldest sons, she ordered them to church for confession. It was wartime and the priest, a Javanese, had been a replacement for the Dutch priest who had been arrested and interned by the Japanese. (His finely chiselled face still hangs on the portrait wall of his memory.) Joost entered the confessional and began his usual and hitherto accepted patter but was cut short by the priest.

“Stop this rubbish. Go outside, think about your sins and come back after the next person,” he ordered.

Joost walked out, surprising his brother,Ed, who had been flirting with a girl and not expecting him to make such a fast exit. Ed entered the confessional whilst he sat in the pew alongside, trying to concoct different lies which he could parrot off on re- entering that silent cubicle which always seemed hostile to him, this home of righteousness that, in his opinion, was a device for hiding the truth. He knelt down and again, began his routine. He suddenly stopped, sick of this stupidity which was supposed to cleanse him but never did, his soul and heart melding with a dispiriting defeat.

“ Where does this start, child? When?” asked the priest, this time in a much gentler tone.

“ I have nothing to confess because I did nothing. Just lived. I am here because my mother gets hurt if I don't come.”

Deep silence – grave-like in mystery. After what seemed like a long time, the silence was broken,

“Leave. Come back when you remember God.”

He left, feeling nothing inside him, emptied out. It took until he was lying in camp one of those terrible days dying from dysentery, waiting for the flood of shit that had left him daily to end his life that he was reborn. Lying on his thin mattress, debating which would come first, liberation or death, he was overcome with the same spiritual emptiness he felt on the day that chiselled face told him to leave, he felt a sudden surge of exhilaration. He realised that he was in the presence of truth...and that truth was that he had never believed in the ritual of Catholicism.